By Michael Radwanski

(edited by Nick Sousanis)

Throughout Detroit’s history, one road has been a significant part of life for all who live and visit this city. Woodward Avenue is a storied street. Generations young and old can identify with the road ranging from memories of a trip down to Hudson’s via streetcar or cruising by car or catching a baseball game at Comerica Park. Despite its frequency of use, the man it’s named is less well known.

Detroit began as little more then an outpost in the American frontier. The French arrived in 1701 to build a fort and a small trading post. As a result, road names like Dequindre and Chene can be linked directly to people who received land grants from the French crown. Eventually the British took over Detroit, before giving it to the newly formed American government in 1796. At that point, Detroit was still a small settlement.

Augustus Brevoort Woodward was a somewhat eccentric man. He was born in 1774, and changed his name from Elias to Augustus to compliment his obsession with Roman history. He had practiced law in his birthplace of New York, and later moved to Washington D.C. Woodward greatly admired Thomas Jefferson, and the two became friends. This friendship resulted in Jefferson appointing Woodward to be a judge and sent him to Detroit.

In 1805, Michigan became a territory. Jefferson appointed two other judges to join Woodward: Benjamin Witherell and Solomon Sibley. Woodward came to Detroit from Washington on horseback shortly after the initial settlement had burned down – the citizens of Detroit were devastated and homeless. Woodward was quick to take action over the still smoking ruins of the city. Without any direction from governor William Hull, he set out to rebuild Detroit in a whole new way.

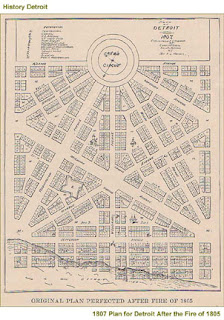

His first plan of action was to get his hands on a set of design drawings by L’Enfant, who had laid out the roads for Washington D.C. This brought a whole new look to the streets of Detroit. L’Enfant’s plan called for streets arranged like the spokes of a wheel that are so familiar to Detroiters today. Woodward named Jefferson Avenue after his friend, but he would only name two other streets after Presidents – Monroe and Madison. While the obvious assumption is that Woodward named the main street after himself, Woodward himself wanted folks to believe otherwise. In fact, he was quite upset when the two other judges in the territory named two minor roads after themselves, Sibley and Witherell. He denied having named Woodward after himself, claiming, “I named it Wood-ward, to the woods” (Bingay 212).

As time went on, Woodward would live up to the title of Caesar. He was in charge of the courts, and without any authority, named himself chief justice. Woodward also wrote his own laws for Michigan, known as The Woodward Code. He held court in the evening on the site of the current city hall building. Court hearings were unruly at best – meat and whiskey were brought in throughout the night. It was at this point that some of the citizens began to be disgruntled with Woodward.

In the War of 1812, Detroit fell to the British without a single shot fired. But even a war could not stop the determined Woodward. He continued to plan the city and received monetary compensation from both the American and the British governments. Woodward planned a community to the north called Woodward Heights. In the midst of playing this massive ego trip with the future of Detroit, he would found the the University of Michigan in the city, modeled after the University of Virginia, which Jefferson founded.

At large, the citizens of Detroit demanded a change, and on March 3, 1824 they got it. President

Monroe got Congress to establish term limits for judges. The news of Woodward having to step down from his position arrived by boat. The citizens could not have been more pleased with Congress. Captain Woodworth had the cannons fired at Detroit to celebrate. Bonfires lit up the sky, as Detroiters partied late into the night. At the Sagina Hotel, Governor Lewis Cass held a banquet along with other leading citizens to celebrate the end of Woodward’s reign.

Despite laying out the city, and founding the University of Michigan, this eccentric and powerful leader was sent on his way. Woodward would accept another judgeship in the state of Florida, but his death shortly after arriving would limit his influence on the region.

Despite laying out the city, and founding the University of Michigan, this eccentric and powerful leader was sent on his way. Woodward would accept another judgeship in the state of Florida, but his death shortly after arriving would limit his influence on the region. Detroiters did everything to dismantle Woodward’s plans except change the name of his street. It stands as a testimony to the city’s colorful past. The next time you venture down Woodward Avenue, take a minute to think about the man, and how his influence is still felt in our city today (Bingay 208-215).

Bingay, Malcolm W. “Detroit is my Own Home Town”. New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1946.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_B._Woodward

No comments:

Post a Comment